Dallas

214-456-2240

Fax: 214-456-8881

Plano

469-497-2501

Fax: 469-497-2507

Request an Appointment with codes: Plastics and Craniofacial Surgery

214-456-2240

Fax: 214-456-8881

469-497-2501

Fax: 469-497-2507

Request an Appointment with codes: Plastics and Craniofacial Surgery

A cleft lip is an opening in the lip, ranging from a small split to a larger gap that extends to the nose. Cleft palate is an opening in the roof of the mouth that, like cleft lip, can also vary in size. Someone can have cleft lip and/or cleft palate. Patients with clefts of the palate only (isolated cleft palate) have different inheritance patterns and characteristics from patients with cleft lip and palate or cleft lip alone.

Cleft lip and palate is the most common congenital anomaly of the face and skull, affecting approximately 1 in 600 newborns in the U.S. Of those children born with a cleft:

There are several factors that may increase the risk of having a child with cleft lip and palate. While the inheritance of many genes from either parent and the maternal use of certain medications and substances (maternal smoking, anticonvulsants, alcohol, retinoic acid) are believed to increase the risk of having a child with a cleft, the majority of children born with a cleft of the lip or palate have none of these associated factors.

The way that the inheritance of many genes can affect the risk for having cleft of the lip or palate is difficult to understand. A simplified way to think about it is that there are many genes that slightly increase someone’s risk of having a cleft. The more of these genes a person has, the more likely it is that they will have a cleft. However, it is important to understand that in most cases, a family with a parent or child with a cleft still has a low risk of having more children with clefts of the lip and palate.

The most common scenario is that a family will have a child born with a cleft and no other history of a person with cleft lip and palate in either parent’s family. The risk of this family’s next child having a cleft is about 5% (1 in 20). If a family has one parent with a cleft but no children with a cleft, the risk of their next child having a cleft is about 5% (1 in 20). If a family has no parent with a cleft but two children born with clefts, the risk of their next child having a cleft is about 10% (1 In 10). If a family has one parent and one child with a cleft, the risk of their next child having a cleft approaches 20% (1 in 5). In other words, a family with one parent and one child born with a cleft has an 80% (4 in 5) chance of their next child NOT being born with a cleft. So even when several family members have had a cleft, the risk is higher than the average person, but still relatively low.

There are rare exceptions to this such as Van der Woude syndrome, which demonstrates autosomal dominant inheritance where 50% of a family’s children may be born with a cleft. For this reason, genetic testing should be done when there is a strong family history of clefts

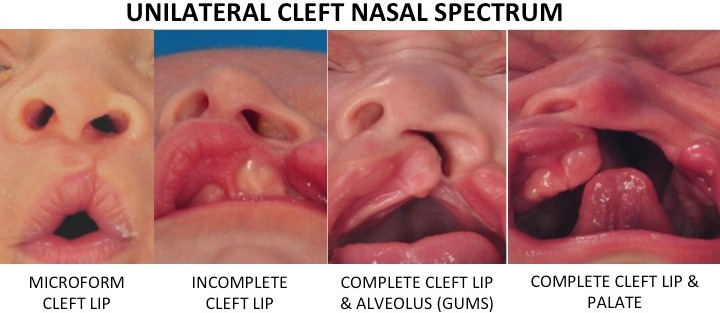

There are two types of cleft lip, unilateral cleft lip and bilateral cleft lip.

Unilateral cleft lip makes up 9 out of 10 of all patients with cleft lip, and is twice as common on the left side as it is on the right. When one side doesn’t reach and connect with the center part of the lip, a unilateral cleft lip occurs. Unilateral cleft lip makes up 9 out of 10 of all patients with cleft lip and is twice as common on the left side as it is on the right. See before and after photos.

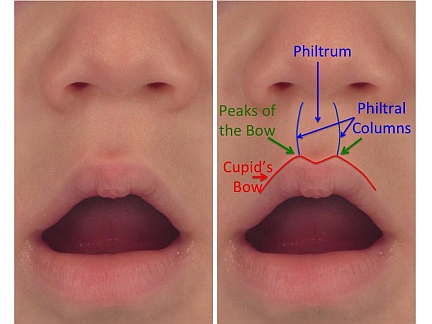

In the image on the right side of the figure above, the baby has a left unilateral cleft lip. The philtral column and the peak of the Cupid’s bow are absent on the left side (the side of the cleft) because the cleft occurs through these structures.

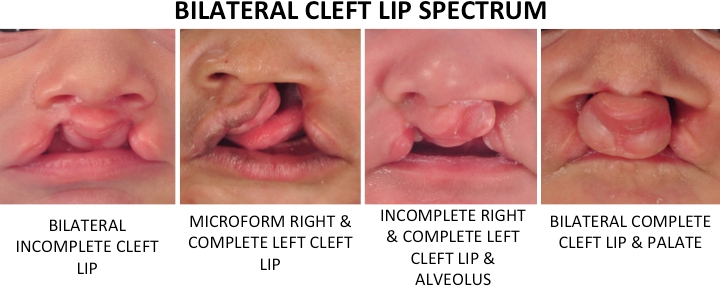

When both the left and right side fail to meet the center part of the lip during prenatal development, a bilateral cleft lip occurs. Bilateral cleft lip is present in only 1 out of 10 patients with cleft lip. See before and after photos.

A unilateral cleft affects the appearance of both the lip and nose depending on the severity of the cleft.

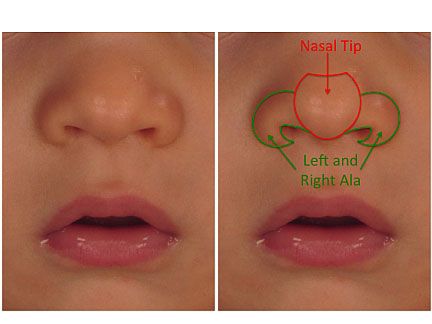

Patients with cleft lip and palate have the most severe changes in the appearance of the lip and nose because the separation in the bones of the gums and palate creates a wide gap that separates the lip segments and drastically changes the shape of the nose. The figure below illustrates some important parts of the nose that are affected by clefts of the lip.

The degree to which the nose is deformed by the cleft of the lip relates to the severity of the cleft of the lip. For the nose, the involvement of the gums and palate have the most dramatic effect on the nasal shape. This is because the cartilage and skin of the nostril (ala) is shaped like an upside down U with the ends of the U sitting on the bone on each side of the cleft. The farther away the ends of the cartilages are from one another, the more severe the deformity of the nostril.

Similarly, the nasal tip and the columella (the skin between the two nostrils) are also affected by the severity of the cleft. The columella is typically shorter on the side of the cleft in unilateral cleft lip. The nasal tip is depressed on the side of the cleft causing significant asymmetry.

When both the left and right side fail to meet the center part of the lip during prenatal development, a bilateral cleft lip occurs. Bilateral cleft lip is present in only 1 out of 10 patients with cleft lip. See before and after photos.

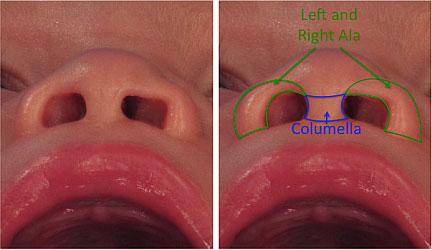

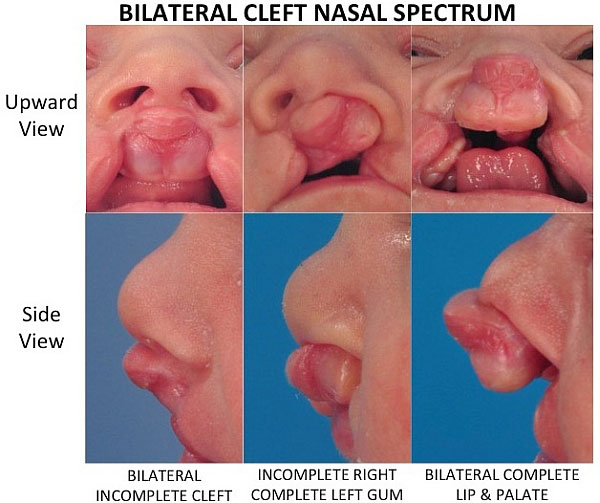

In the image on the right side of the figure above, the baby has a bilateral cleft lip, both the left and right philtral columns and the peaks of the Cupid’s bow are absent. In both unilateral and bilateral cleft lip, the majority of patients will have some involvement of the gums and palate. There is a spectrum of severity for bilateral cleft lip.

In bilateral cleft lip, the two sides of the cleft may be of the same or very different severity. A bilateral cleft affects the lip by causing a shorter central portion of the lip and a change in the quality and bulk of the red portion of the lip (vermillion). In general, the major difference between unilateral and bilateral clefts are the effects of the forward displacement of the bone under the middle portion of the lip (premaxilla). This portion of the upper gums contains the middle four front teeth. This center portion of the lip and gums gets pushed forward by the tongue over the course of the pregnancy.

The most noticeable changes in the nose are seen in the columella, which is severely shortened. The nasal tip tends to be wider with poor definition, and the curve or your nostrils (alar bases) are displaced backward and are wider than normal.

The side view of the infant with complete bilateral cleft lip and palate shown above is seen on the far right. This picture shows the severe forward displacement of the middle part of the upper lip and gums that occurs with complete bilateral cleft lip and palate and how that abnormal position of the gums changes the shape of the nose. The severity of these changes in the nasal shape can be significantly improved by the use of nasoalveolar molding (NAM).

A baby’s upper lip, nose and roof of the mouth (palate) should form completely 10 weeks into the pregnancy. The two sides of the face fuse together at the philtrum, the normal feature found in the middle portion of the upper lip. The lip forms from three parts – the center part and the left and right side parts.

The left and right parts of the lip grow toward the center as the face is formed early during the pregnancy. Normally the side portions meet and fuse with the center portion. The places where the center and side portions of the lip fuse become the philtral columns. These are the raised ridges extending the vertical length of the lip up to the nose.

The Cupid’s bow is the normal shape of the lip where the red and white portions of the lip meet. The philtral columns meet the lip at the peaks of Cupid’s bow. When these sides do not meet, a cleft lip forms.

Children with cleft lip and palate require specialized care by a cleft team from the time of their birth until they are fully grown. Excellent long-term functional and aesthetic results are the product of a well-coordinated treatment plan through collaboration of all members of the team.

Our care team includes speech-language pathologists (SLPs), including a bilingual SLP to offer special insight into the speech and language development of our Spanish-speaking cleft population.

The American Cleft Palate Association (ACPA) recommends a team approach to the treatment of cleft and craniofacial patients. It has created strict requirements to achieve certification as an ACPA-designated team.

The ACPA defines that the purpose of the Cleft and Craniofacial Team “is to ensure that care is provided in a coordinated and consistent manner with the proper sequencing of evaluations and treatments within the framework of the patient’s overall developmental, medical and psychological needs.” The Cleft and Craniofacial Team at Children’s is proud to be an ACPA-designated team.

The mission of the Cleft and Craniofacial Team at Children’s is to provide comprehensive care for patients with cleft lip and palate and craniofacial anomalies. Team care includes a collaborative evaluation and treatment planning by all of the specialists that will be active in caring for the patient throughout his/her childhood.